WASHINGTON â In an afternoon's walk through the Smithsonian's , objects around every corner invite one question: What could possibly be more American than this?

The museum explores "the complexity of our past" in accord with its mission statement. There's the enormous , Dorothy's from "The Wizard of Oz" and totems of achievement throughout.

There are also testaments to pain and cruelty, illustrated by shackles representing slavery and photos of in World War II.

People are also reading…

President Donald TrumpĚýwants Smithsonian museums to mirror American pride, power and accomplishment without all the darkness, and threatened to hold back money if they don't.

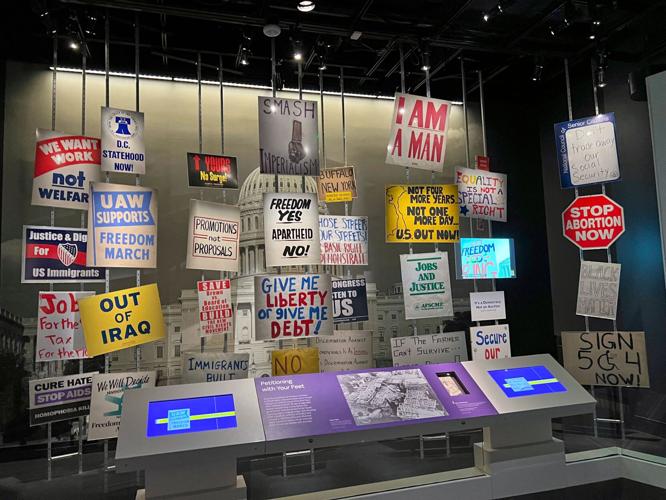

This wall in the âGreat Debateâ section of a democracy exhibit is seen Aug. 26Ěýat the National Museum of American History in Washington.

Genius and ugliness on display

On social media, Trump complained that at the Smithsonian museums, which are free to visit and get most of their money from the government, "everything discussed is how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was, and how unaccomplished the downtrodden have been â Nothing about Success, nothing about Brightness, nothing about the Future."

In fact, the history museum reflects bountiful successesĚýâ on battlefields, from the kitchens and factories of food pioneers, on the musical stage, in the movies or on other fronts of creativity and industriousness. The , for one, has a wall filled with stories of successful Americans.

On this wandering tour you can see navigational implements used by the pirate Blackbeard from his early 1700s raids on the Atlantic coast. You see the hat Abraham Lincoln wore to Ford's Theatre the night of his assassination, George Washington's ceremonial uniform, Warren Harding's red silk pajamas from the early 1900s, the first car to travel across the United States, and a $100,000 bill.

You can see the original light bulbs of the American genius Thomas Edison. Founding father Benjamin Franklin is presented as a gifted inventor and a slave owner who publicly denounced slavery yet never freed his own.

Protest signs from a selection of historic demonstrations are displayed Aug. 13 at the Smithsonianâs National Museum of American History in Washington, representing the causes of anti-war and civil rights activists, the tea party, farmers and other populist movements.

Those nuances and ambiguities may not be long for this world. Still on display at the history museum are artifacts and documents of American ingenuity, subjugation, generosity, racism, grit, dishonor, verve, playfulness, corruption, heroism and cultural appropriation.

In the "Great Debate" of an American democracy exhibition, a wall is emblazoned with large words including "Privilege" and "Slavery." The museum presents fulsome tributes to the contributions of immigrants and narratives about the racist landscape that many encountered.

Exhibits address "food justice," the exploitation of Filipinos after the U.S. annexed their land and the network of oppressive Native American boarding schools from which Jim Thorpe emerged and became one of the greatest athletes of all time.

A âFight the Virus, Not the Peopleâ COVID-19 banner, which was carried by counter-protesters at an anti-Asian hate march in San Francisco in February 2020,Ěýis displayedĚýAug. 13Ěýat the museum.

Hawaii's last sovereign before its annexation by the U..S. in the 1890s, Queen Lili'uokalani, is quoted on a banner as asking: "Is the AMERICAN REPUBLIC of STATES to DEGENERATE and become a COLONIZER?"

A ukulele on display was made about 1890 by a sugar laborer who worked on the kingdom's American plantations before a U.S.-backed coup overthrew the monarchy. Museum visitors are told the new instrument was held up by the monarchs as a symbol of anti-colonial independence.

"Ukuleles are both a product of U.S. imperialism and a potent symbol of Native Hawaiian resistance," says the accompanying text.

The White House is ordering a review of the Smithsonian museums to align content with President Donald Trump's interpretation of American history.

American spirit celebrated, too

At the Greek-godlike statue of George Washington, the text hints at his complexities and stops short of the total reverence that totalitarian leaders get.

Noting that "modern scholarship focuses on the fallible man rather than the marble hero," the text says Washington's image "is still used for inspiration, patriotism and commercial gain" and "he continues to hold a place for many as a symbolic 'father' of the country."

Conservators are the museum are restoring the , part of a small fleet that engaged the British navy at the Battle of Valcour Island in Lake Champlain in 1776, delaying Britain's effort to cut off the New England colonies and buying time for the Continental Army to prepare for its decisive victory at Saratoga.

The commander of the gunboats in the Valcour battle later became America's greatest traitor, Benedict Arnold. The British damaged the Philadelphia so badly, it sank an hour after the battle, lying underwater for 160 years. It's being restored for next year's celebrations of America's 250th year.

"The Philadelphia is a symbol of how citizens of a newly formed nation came together, despite overwhelming odds against their success," said Jennifer Jones, the project's director. "This boat's fragile condition is symbolic of our democracy; it requires the nation's attention and vigilance to preserve it for future generations."

A new sign is displayed Aug. 26 at the presidential impeachment exhibit at the museum in Washington, describing the counts against President Donald Trump in his second impeachment trial.

Itâs not telling you what to think, but what to think about

Democracy's fragility is considered in a section about the limits of presidential power. That's where references to Trump's two impeachments were for updating, and were restored in recent days.

"On December 18, 2019, the House impeached Donald Trump for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress," one label now states. "On January 13, 2021, Donald Trump became the first president to be impeached twice," another says. "The charge was incitement of insurrection based on his challenge of the 2020 election results and on his speech" on Jan. 6, 2021, that precipitated his supporters' attack on the U.S. Capitol. His Senate acquittals are duly noted.

It's a just-the-facts take on a matter that drove the country so deeply apart.

An updated display at the museum, seenĚýAug. 26, traces the history of presidential impeachments.

The history museum doesn't offer answers for such predicaments. Instead, it asks questions throughout its halls on the fundamentals of Americanism.

âHow should Americans remember their Revolution and the founding of the nation?â

âWhat does patriotism look like?â

âHow diverse should the citizenry be?â

âDo we need to share a common national story?â

The history and significance of Juneteenth

![]()

The history and significance of Juneteenth

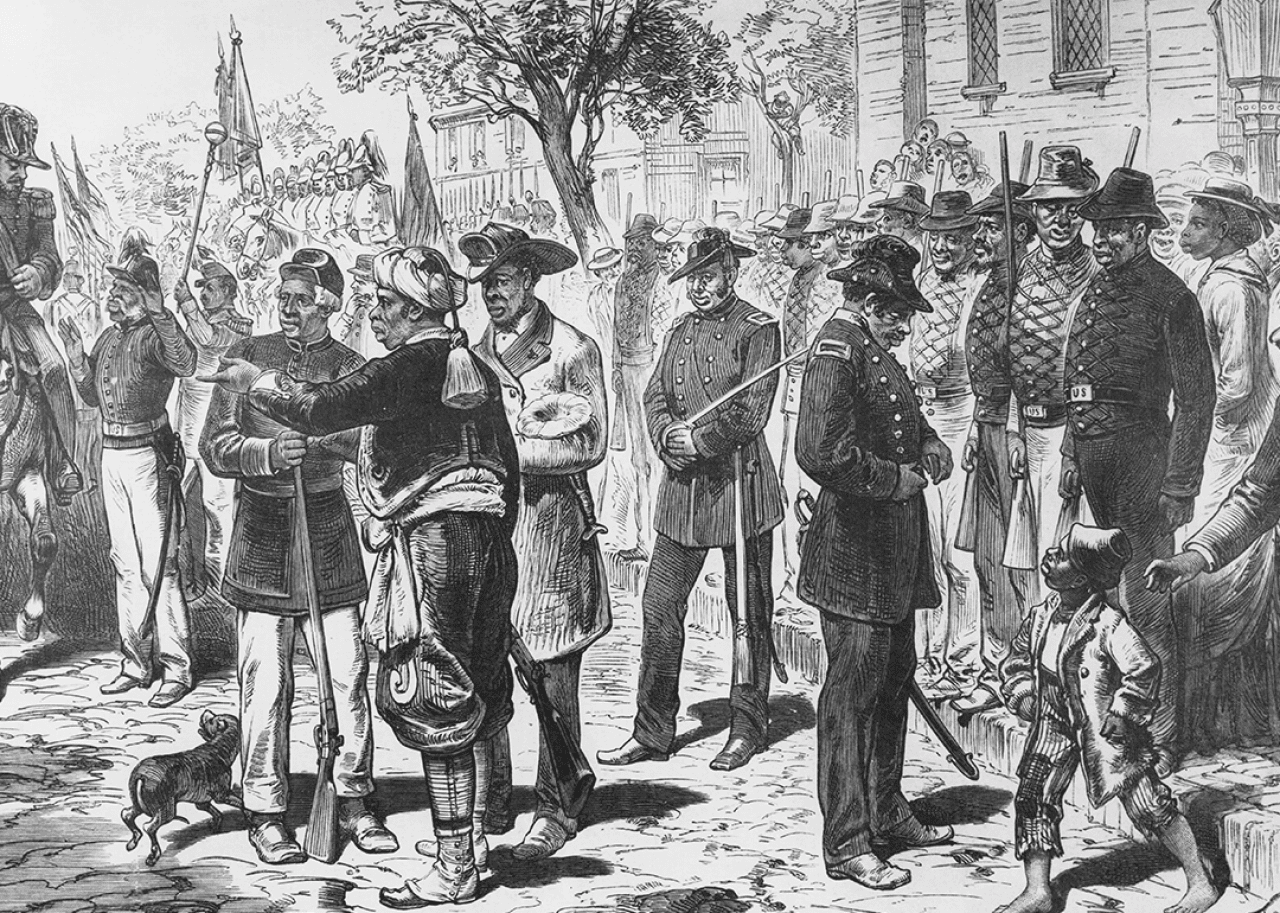

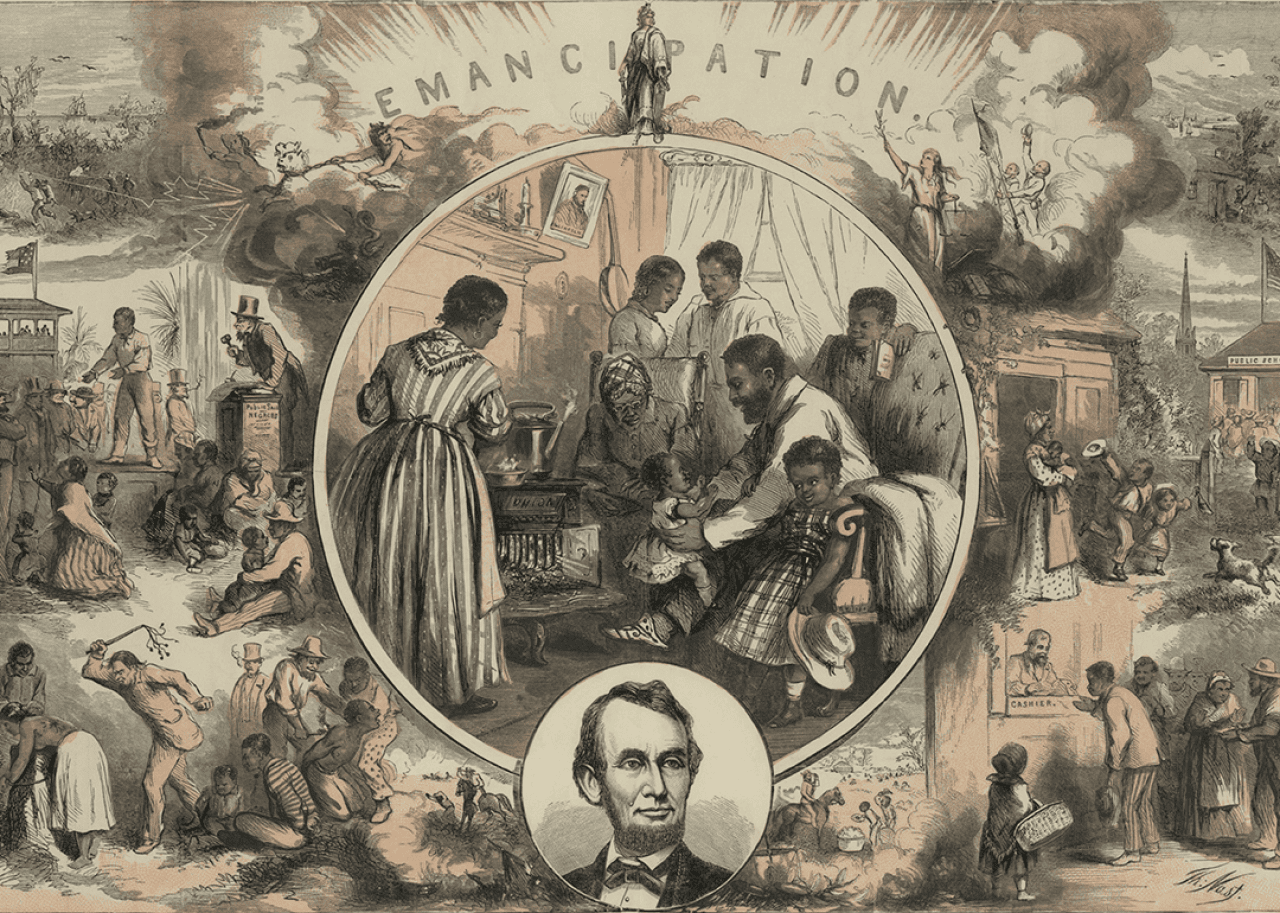

Juneteenthâalso known as Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, or the country's second Independence Dayâstands as an enduring symbol of Black American freedom. When Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger and fellow federal soldiers arrived in Galveston, a coastal town on Texas' Galveston Island, on June 19, 1865, it was to issue orders for the emancipation of enslaved people throughout the state.

Although telegraph messages had spread news of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and while the war had been resolved in the Union's favor since April of 1865, Granger's message represented a promise of accountability. There was now a large enough coalition to enforce the end of slavery and to overturn the Texas Confederate constitution, which forbade individuals' release from bondage.

In this way, Texas became the last Confederate state to end slavery in the United States.

Though celebrated for hundreds of years in parts of the U.S., Juneteenth's history and significance have only recently gained massive national attention. The historic date was not recognized as a federal holiday until 2021, more than a century and a half after it took place.

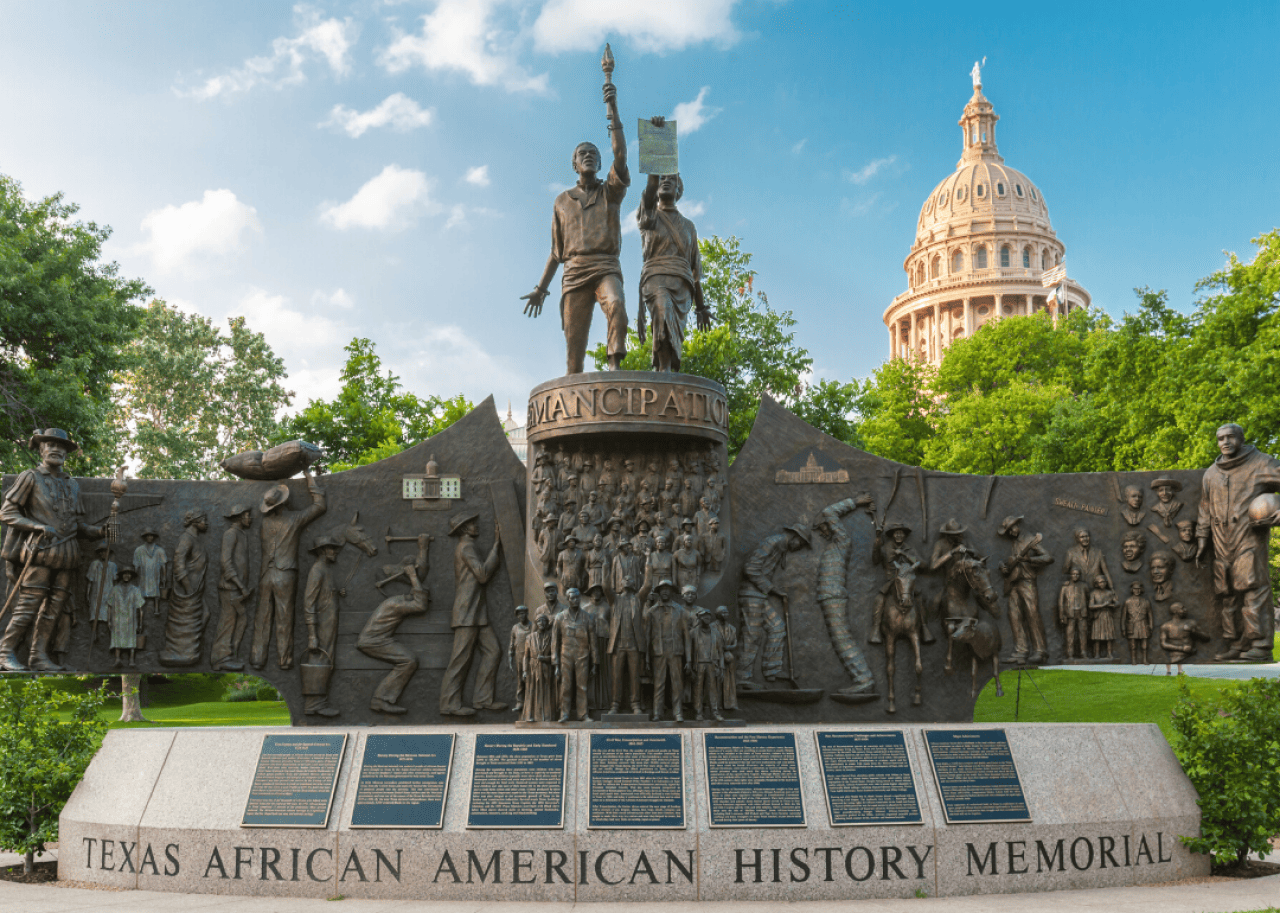

Today, Juneteenth is commonly commemorated with public art, festivals, and civic engagement across the country. In 2025, the long-awaited National Juneteenth Museum , guided by the staunch efforts of activist , who is widely regarded as the "Grandmother of Juneteenth." Meanwhile, cities like Atlanta, Detroit, and Philadelphia have expanded their Juneteenth programming, incorporating everything from economic justice panels to .

The holiday has also sparked renewed debates over how schools teach slavery and Reconstruction, particularly in light of state-level restrictions on curricula addressing racism and Black history. In this moment, Juneteenth has become not just a day of remembrance; it's a reflection of ongoing struggles for equity and historical truth.

explored the history and significance of Juneteenth by examining historical documentation, including texts for General Order #3 and the Emancipation Proclamation. Stacker also researched the lasting significance of this historic day while clarifying some of the most egregious misinformation about it.

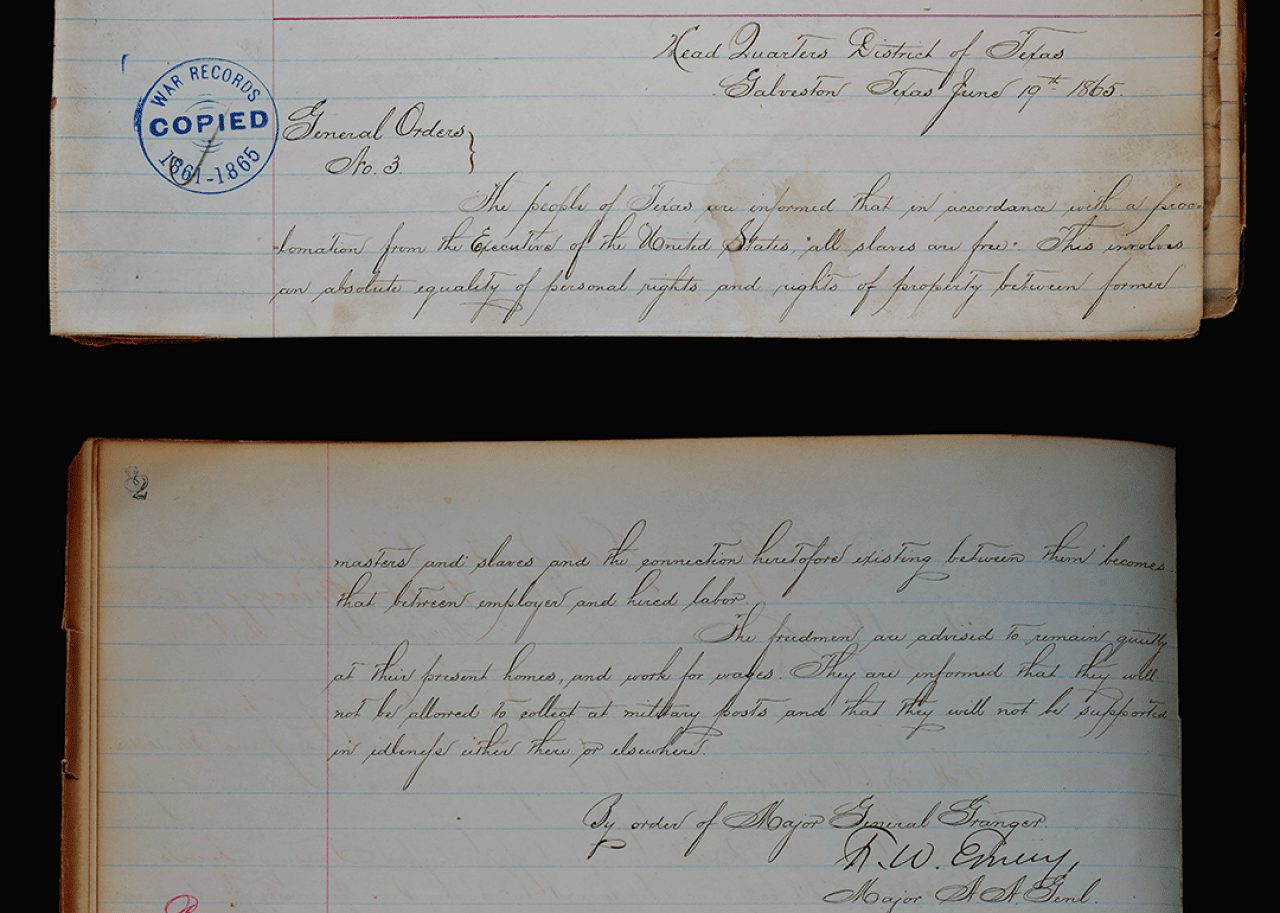

Juneteenth commemorates the 1865 delivery of General Order #3

Maj. Gen. Granger was given command of the District of Texas following the Civil War's conclusion, making him an obvious choice for delivering General Order #3.

In its simplest terms, declared that all enslaved people in Texas were free; but the order maintained racist undertones and encouraged enslaved people to stay where they were being held to continue workâthis time for wages as free men and women.

The order's , preserved at the National Archives Building in Washington D.C., reads:

"The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."

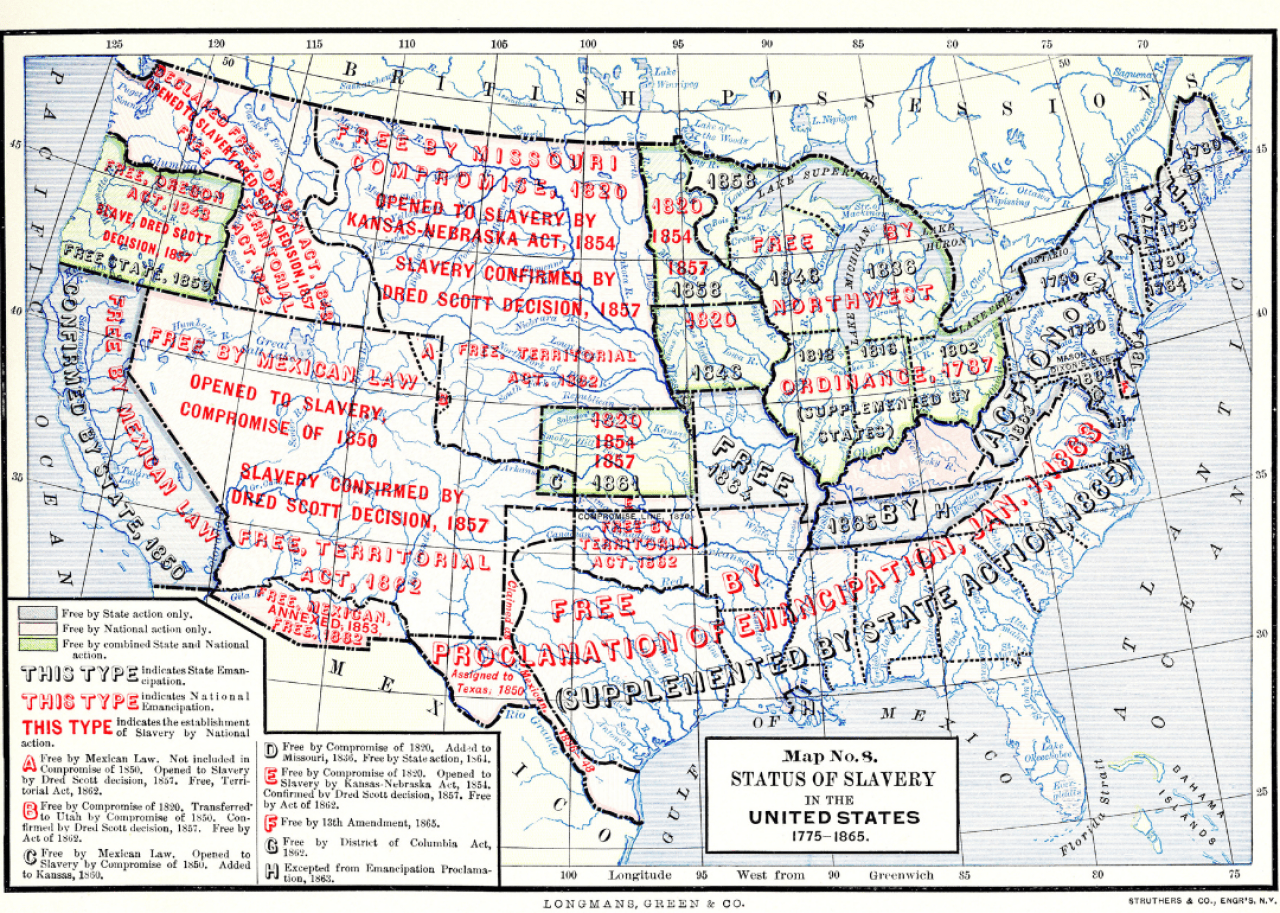

Chattel slavery in all states wasn't abolished until the end of 1865

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed into law by President Lincoln on Jan. 1, 1863, called for an end to legal slavery in secessionist Confederate states only, impacting about 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country at that time. As the war drew to a close and Union soldiers retook territory, enslaved people living in those areas were liberated.

Lincoln's decision to free only those enslaved individuals in bondage in Confederate states was a strategic, militaristic method, as he notably did not free those enslaved in Union states. Further, the proclamation was unenforceable. Still, Union troops fighting in the war brought news of emancipation along with the military might to enforce it. Many enslaved people were motivated enough by the news to risk fleeing and seek safety in Union states or by joining the U.S. Army and Navy to help fight.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, any enslaved person who escaped over Union lines or to oncoming federal troops during the war was free in perpetuity.

Maj. Gen. Granger's orders on June 19, 1865, released enslaved people in Texas from bondage. But it was another six months before the last two statesââfreed enslaved people, and only when the 13th Amendment was ratified on Dec. 18, 1865.

The 13th Amendment officially ended slavery and involuntary servitude at the federal level, except as a punishment for a crime. That loophole has been capitalized upon since the amendment passed. Kentucky officially in 1976.

Juneteenth celebrations originated in Galveston, Texas, starting in 1866

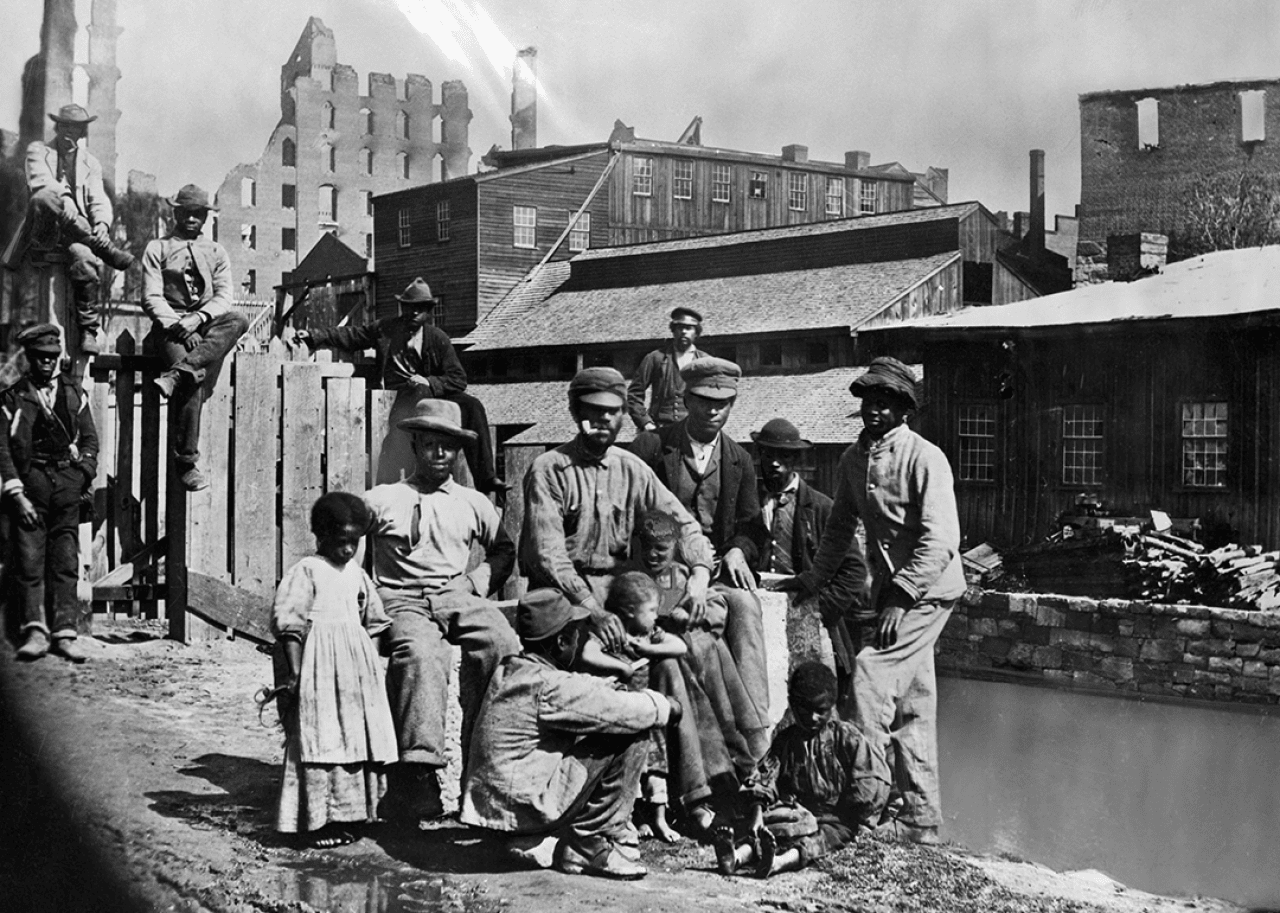

Mixed reactions followed .

Many newly freed people remained on former enslavers' properties to work for pay, while others immediately fled north or into nearby states like Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma to reunite with family. As people fanned out around the country, they took Juneteenth celebrations along with them. Formerly enslaved people and their descendants also made yearly pilgrimages back to Galveston to memorialize the date's significance.

Juneteenth became an official Texas holiday in 1980.

While Juneteenth is among the oldest celebrations of emancipation, it is not the oldest. That distinction goes to Gallipolis, Ohio, which has celebrated the end of slavery there since Sept. 22, 1863.

The first land to commemorate and celebrate the event was purchased in 1872 and is now a public park

Formerly enslaved African American ministers and businessmen got together in 1872 to raise the $1,000 necessary to buy 10 acres of land in Houston's Third and Fourth wards. They called the lot .

The park was donated to the city of Houston in 1916. In the late 1930s, the Public Works Administration, which was established as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, constructed a recreation center and public pool on the park site. The Houston City Council declared the park a protected historic landmark on Nov. 7, 2007.

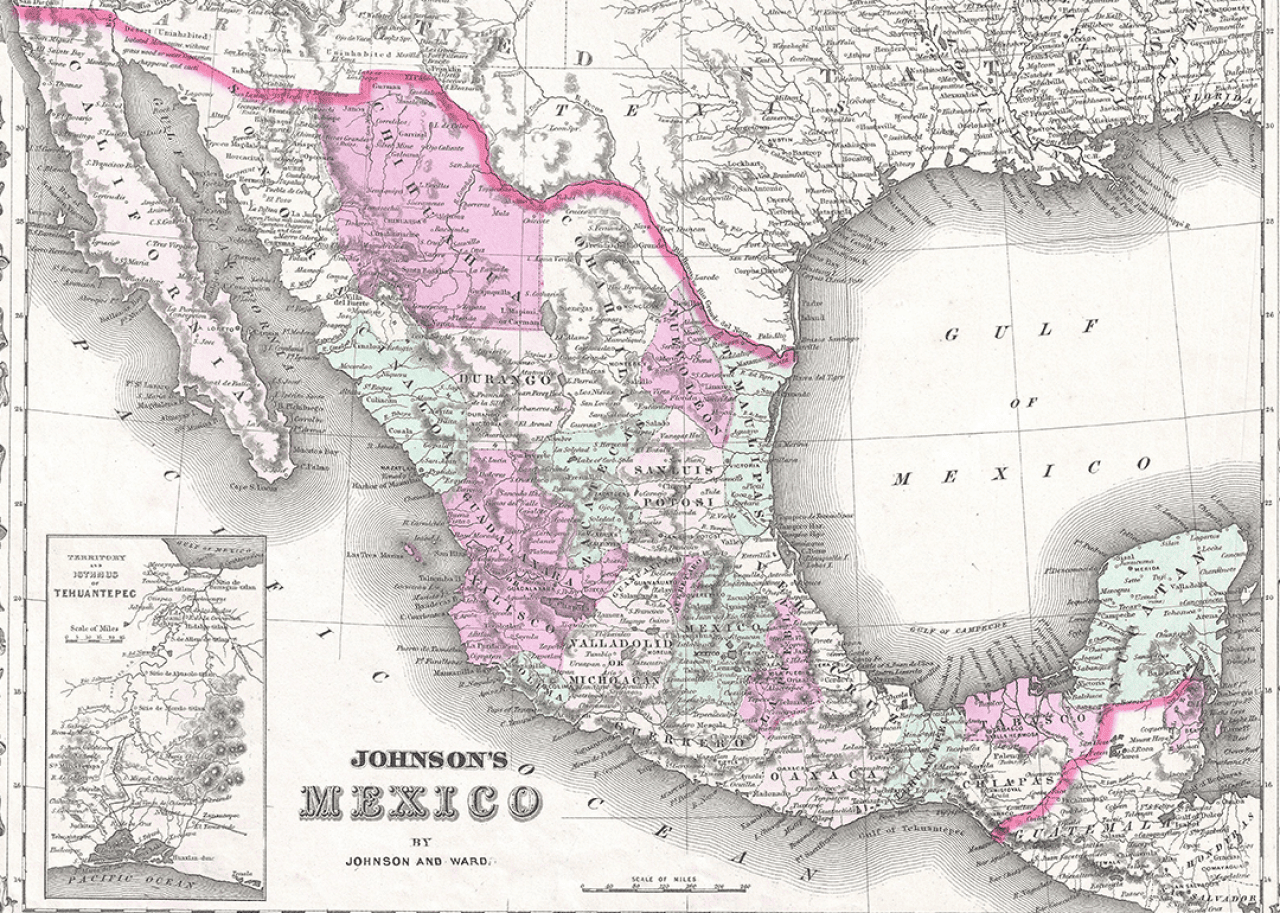

Juneteenth has been celebrated in Mexico for more than 150 years

Mexico was a longtime sanctuary for those who escaped chattel slavery, with a that helped as many as 10,000 people flee bondage. Descendants of enslaved people who also emigrated over the southern border from the U.S. brought with them a tapestry of histories and traditions, including the Juneteenth celebration.

Juneteenth has been celebrated in a small Mexican village called Nacimiento since 1870.

The last enslaved people in the US weren't adopted as citizens until 1885

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War and had members who enslaved Black women, children, and men. Following the Civil War's conclusion, the Choctaws did not grant those who were enslaved their freedom.

The called for the Choctaws to free the enslaved Africans in exchange for $300,000 paid by the U.S. government to the Choctaws and the Choctaw Nation. Many of those liberated chose to stay and live as free people among the tribal communities. More than 100 years later, in 1983, Choctaw voters adopted a that declared all members "shall consist of all Choctaw Indians by blood whose names appear on the original rolls of the Choctaw Nation ⌠and their lineal descendants," all but expelling Freedmen citizens from citizenship within tribal communities.

Festivities became more commercialized in the 1920s during the Great Migration

Early Juneteenth celebrations were spent in prayer and with family but eventually expanded to include everything from rodeos and baseball to certain foods like strawberry soda pop and barbecues. Food has long been central to Juneteenth, as participants often arrive with their own dishes.

Attention for Juneteenth waned in the early 20th century as classroom instruction veered away from the history of enslavement in the U.S. and instead taught that slavery ended in one fell swoop with the Emancipation Proclamation.

Juneteenth officially became a Texas state holiday in 1980

Texas was the last Confederate state to free enslaved people from bondage, but it was also the first to make Juneteenth an official state holiday.

The late Texas Rep. Al Edwards put forth a bill in 1979 called that was entered into state law later that year and went into effect on Jan. 1, 1980. It was before another stateâFloridaâpassed a similar law of recognition.

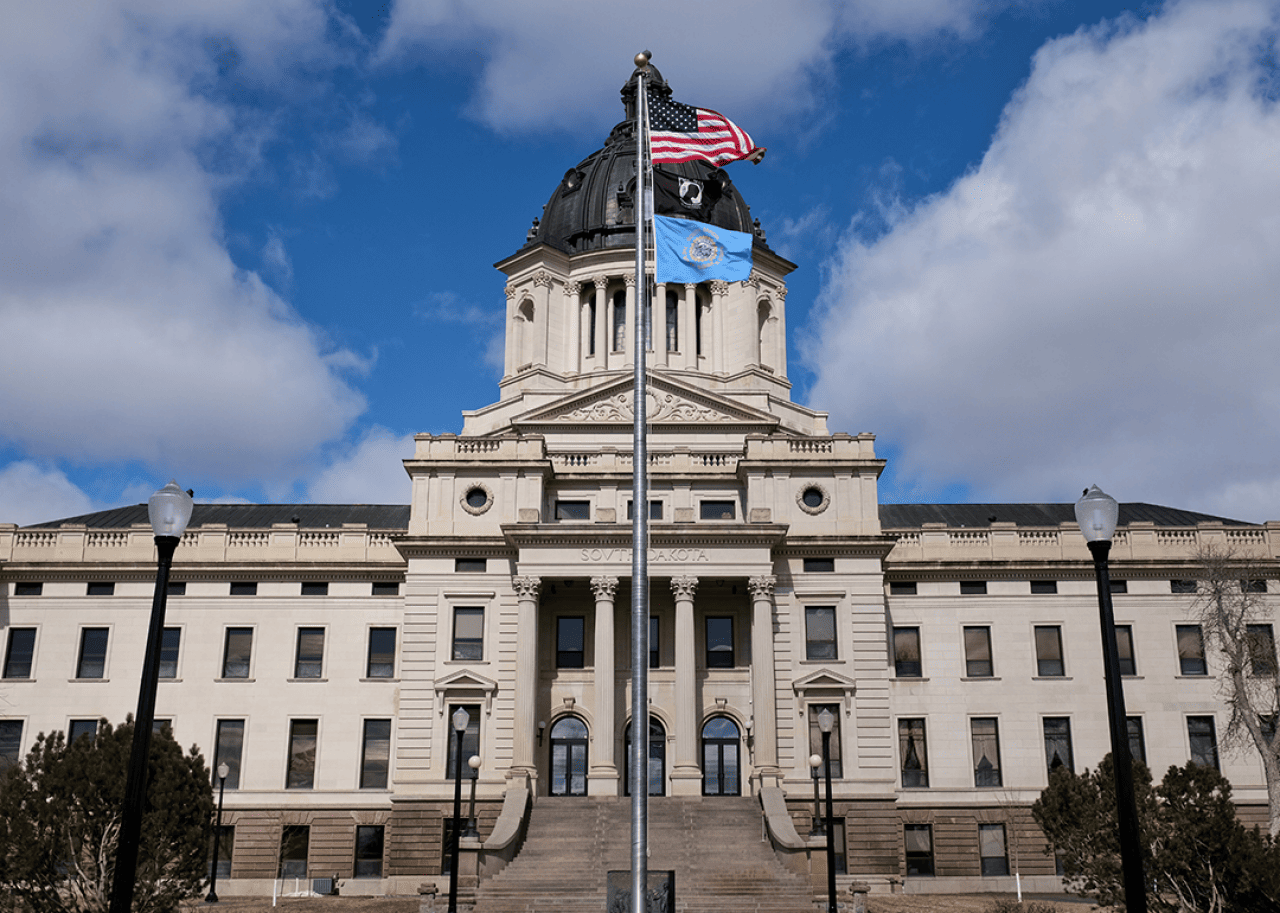

South Dakota was the last state to make Juneteenth a legal holiday

In February 2022, Gov. Kristi Noem signed HB 1025 to recognize Juneteenth as a legal holiday.

preceded South Dakota by about eight and 10 months, respectively.

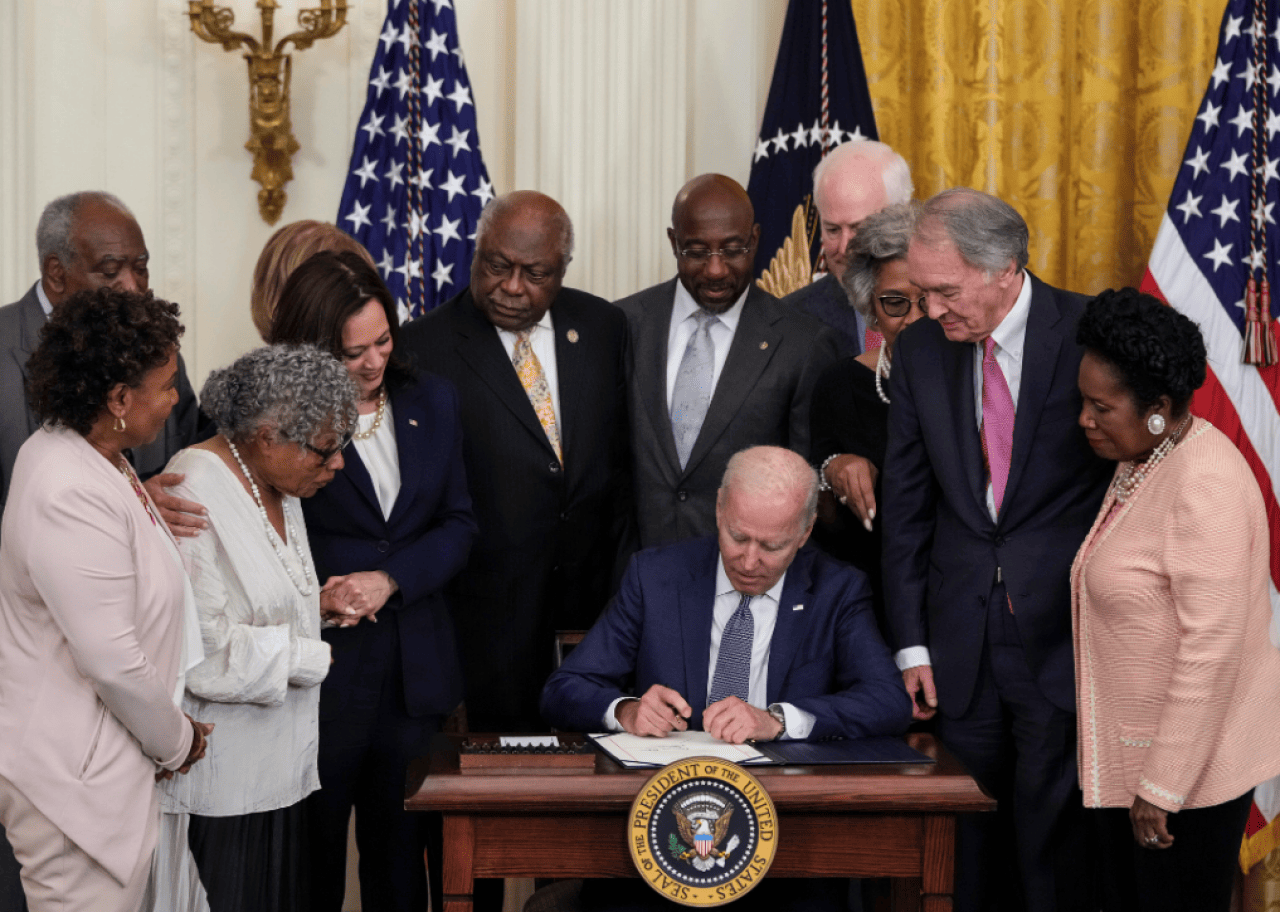

Juneteenth wasn't recognized as a federal holiday until 2021

Juneteenth achieved increasing recognition in recent decades, but the full embrace of the celebration as a national holiday following the murder of George Floyd on May 20, 2020. The resultant Black Lives Matter protests that erupted worldwide in a stance against acts of racial injustice and police brutality spurred corporations nationwide to support Juneteenth as an act of allyship, and things snowballed from there.

The following year, President Joe Biden signed a bill in June 2021 officially declaring Juneteenth a national holiday. Juneteenth was the first new federal holiday since 1983 (MLK Jr. Day) after .

Additional writing and copy editing by Paris Close.

Juneteenthâalso known as Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, or the countryâs second Independence Dayâstands as an enduring symbol of Black American freedom.

When Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger and fellow federal soldiers arrived in Galveston, a coastal town on Texasâ Galveston Island, on June 19, 1865, it was to issue orders for the emancipation of enslaved people throughout the state.

Although telegraph messages had shared news of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and while the war had been settled in the Unionâs favor since April of 1865, Grangerâs message was a promise of accountability. There was now a large enough coalition to enforce the end of slavery and overwhelm the Texas Conferedate constitution, which forbade individualsâ release from bondage.

In that way, Texas became the last Confederate state to end slavery in the U.S.

Though celebrated for hundreds of years in parts of the U.S., Juneteenthâs history and significance only recently scaled for a massive national audience and inflection point. The historic date was not recognized as a federal holiday until 2021âmore than a century and a half after it took place.

explored the history and significance of Juneteenth by examining historical documentation including texts for General Order #3 and the Emancipation Proclamation. Stacker also researched the lasting significance of this historic day while clearing up some of the most egregious misinformation about it.

You may also like:

![]()