Harry Clark was practicing his cello when a fellow Interlochen summer camper rushed in.

You got a phone call from home, the boy told Clark, who was understandably alarmed.

ŌĆ£You never got phone calls from your parents,ŌĆØ Clark recalled. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs hard to even locate you. But I remember this little kid, he was in junior high, came running and found me in some little hut that I was practicing in.ŌĆØ

Harry Clark and Sanda Schuldmann met in college and formed a lifelong musical partnership that included Chamber Music Plus Southwest, which they ran in Tucson for nine years.

He hadnŌĆÖt heard from his family in Tucson since he arrived at Interlochen Center for the Arts in Michigan six weeks earlier.

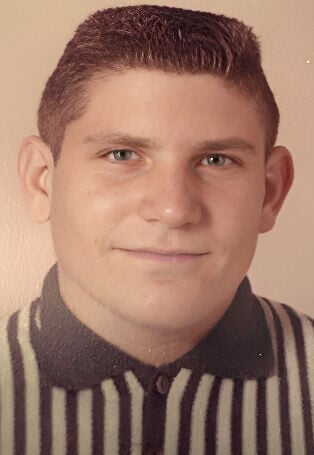

Clark ran with the boy across campus to the campŌĆÖs main office, which had the only phone; it was 1965, way before the advent of cellphones or laptops.

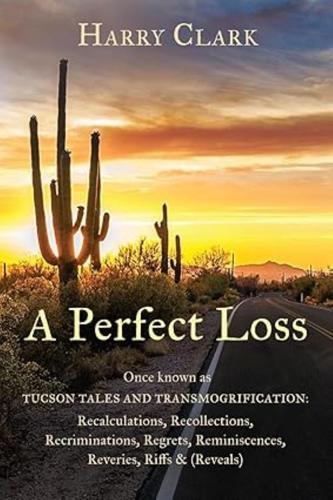

ŌĆ£The entire conversation could not have been more than a minute or two, the connection scratchy, the message nearly incomprehensible,ŌĆØ Clark recounted in his just released fictional memoir ŌĆ£A Perfect LossŌĆØ (self published via BookLocker). ŌĆ£My mother on the other end: ŌĆśYour father has gotten a new job in Annapolis, Maryland, that is, and instead of your returning to Tucson we will be coming to Interlochen to pick you up and proceeding East from there.ŌĆÖ That was it. The meter running. Just the facts maŌĆÖam. And it plays out exactly in this fashion. I do not return. I do not say good-bye; I do not pass go.ŌĆØ

People are also reading…

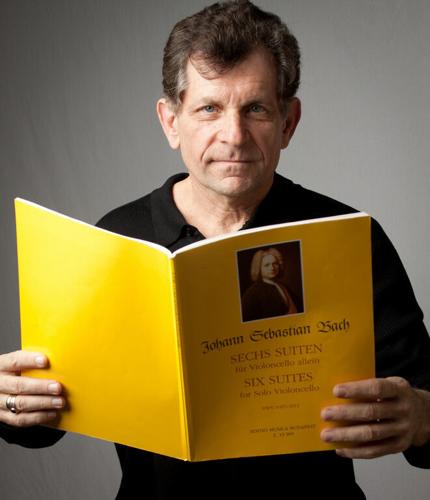

Retired Tucson cellist Harry Clark just released his self-published memoir, ŌĆ£A Perfect Loss.ŌĆØ

Instead of finishing high school at Palo Verde with friends from his east-side Tucson neighborhood, Clark was thousands of miles away, graduating with strangers from a Maryland school before heading off to the University of Texas in Austin, where he met his wife, pianist Sanda Schuldmann.

Over the years, he visited Tucson, but never the old neighborhood ŌĆö he calls it B Street in the book. Even after he moved back home in 2002, he didnŌĆÖt reach out to reconnect.

ŌĆ£I hadnŌĆÖt really thought of them,ŌĆØ he said.

Until his cancer diagnosis in 2011.

ŌĆ£When you start thinking about mortality, you start thinking about these people a lot,ŌĆØ Clark said.

The kids from his childhood reappeared in the dreams that came not long after Clark was diagnosed with melanoma.

Cellist Harry Clark wrote nearly 70 ŌĆ£musical portraitsŌĆØ of historical classical music figures as part of his Chamber Music Plus program. Big name actors would do dramatic readings of his scripts while he and his pianist wife Sanda Schuldmann would perform the music.

ŌĆ£For a while there ... I wasnŌĆÖt doing that great, and I began to have these dreams about kids that I grew up with on B Street,ŌĆØ he said.

Those dreams led Clark to write his memoir, trying to recreate an interrupted childhood and reconnect with a cast of characters that impacted his life long after he left.

Back to B Street

B Street was in many ways your typical middle-class neighborhood with its mix of characters and wallflowers.

It also had dark secrets and trauma that Clark and his friends experienced in real time.

In his fever dreams, Clark was back in the old neighborhood with his best friend Mikey and verbally sparring with MikeyŌĆÖs older brother Roy about bullfighting and the Pittsburgh Pirates 1959 ŌĆ£perfect game,ŌĆØ the one where Harvey Haddix pitched 12 perfect innings and lost the game in the 13th. He and Roy went back and forth over the same question: How can you have a perfect game and still lose?

There was Nervous, the kid from across the street who was two years younger, wore thick glasses and had a tic, but nearly on the daily, he would cut through the alley and into ClarkŌĆÖs backyard to play ping pong. By ClarkŌĆÖs count, he and Nervous mustŌĆÖve played thousands of games.

Even after NervousŌĆÖs father killed himself, a gunshot to the head that rattled the neighborhood, Nervous showed up for ping-pong.

ŌĆ£Days later we resume ping-pong and for a year or so we continue our play with the same constancy, the same intensity,ŌĆØ Clark wrote. ŌĆ£Surely it was my duty to say something, anything. Perhaps the game was conversation enough. No, too easy.ŌĆØ

Clark

He dreamed about that cold February day in 1965 when he debated the merits of ŌĆ£The Addams FamilyŌĆØ vs. ŌĆ£The MunstersŌĆØ with Curt T, a kid too cool to follow the rules, who called his mom Lola and lived in a big house blocks away from B Street.

It was the last time Clark saw him.

Two days later, CurtŌĆÖs father, Tucson chiropractor George Tegerdine, was arrested for killing Wilbur Hanson and stuffing his body in his trunk; he was later convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Lola left Tucson with Curt and his sisters and never returned.

ClarkŌĆÖs dreams conjured up Mitch B, the neighborhood bad boy who was obsessed with Tucson serial killer Charles Schmid, the so-called ŌĆ£Pied Piper of Tucson.ŌĆØ Mitch loved to talk about the details of SchmidŌĆÖs murders of three Tucson high school girls. Schmid got the death sentence that was later commuted to life, but he ended up getting killed in prison.

Family ties that donŌĆÖt bind

A throughline of his dreams was ClarkŌĆÖs feeling about where he fit on B Street and in his own home.

ŌĆ£There was a period of about 18 months where I would think, now looking back, that if I were that age now, I would probably be in some computer chatroom somewhere and even more lost,ŌĆØ Clark said.

He was a junior in high school that year that all the trauma unfolded on B Street, juggling advanced classes to boost his college applications. Those classes meant nothing to his future as a cellist so he didnŌĆÖt put in the effort and almost failed.

Cellist Harry Clark and his wife, pianist Sanda Schuldman, lived in Tucson from 2002 until 2023, when they moved to Ohio.

He also was butting heads with his parents over his desire to become a musician. They didnŌĆÖt get it; there were no musicians in the family, no examples to follow on how music could be more than a hobby.

ŌĆ£They couldnŌĆÖt understand what it meant to be a musician, what I needed to succeed,ŌĆØ Clark said, which caused a rift in the relationship and also sent him into a deep morose. ŌĆ£But these guys, Mikey and Roy and Mitch, all these guys on B Street, they didnŌĆÖt give a damn about that. They took me for what I was, and I owe them. I was the weird guy playing the cello but they never held that against me.ŌĆØ

Then came the suicide and the murder, traumas that affected him personally but didnŌĆÖt quite register with his parents. They never talked about it, as if silence was the key to pretending it never happened.

ŌĆ£I felt I couldnŌĆÖt relate to my family,ŌĆØ Clark said. ŌĆ£I felt more drawn towards all these kids. I had my music friends, too, but I had this other subset of friends that were the guys that really kept me from going under and having some kind of major breakdown. They kind of accepted me as I was.ŌĆØ

A cathartic experience

Clark started writing ŌĆ£A Perfect LossŌĆØ 10 years ago, after his bout with cancer. It started as a play, a conversation with those ghosts from B Street that haunted his cancer dreams.

But it evolved into a story that was more connecting the dots of lost time.

Clark, who had just retired from a 40-year career writing screenplays for his classical music-meets-theater program Chamber Music Plus Southwest, started searching for his childhood friends.

He ran into dead ends and an obit or two until he got to Mitch.

Mitch, who as a kid was obsessed with murder and had a reputation for not following the straight and narrow, grew up to be a murderer.

His real name was Mitchell Thomas Blazak and in 1973 he was convicted of killing a bartender and patron at a Tucson bar during a botched robbery attempt. Blazak spent years appealing his case and was finally successful in 1997. To avoid a retrial, he pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was released from prison for time served. He later died in a bizarre tractor accident.

Clark searched court documents and found his lawyer, Thomas Higgins. He still lived in Tucson and when he called him and told him he had known Blazak when they were kids, the lawyer agreed to meet.

Higgins, as it turned out, grew up in the same neighborhood as Clark.

ŌĆ£He lived within a couple blocks of where I lived on B Street and he knew every one of the people,ŌĆØ Clark said. ŌĆ£I think he was struck by ŌĆśhow is this possible that we never at least bumped into one anotherŌĆÖ.ŌĆØ

Higgins, who has a recurring role as fact checker in ŌĆ£A Perfect Loss,ŌĆØ was able to connect the dots to some of the loose ends Clark left behind that summer of 1965. Little details, like how Higgins heard the gunshot on the day that NervousŌĆÖs father killed himself.

ŌĆ£Yeah, I thought it was Mitch clowning about,ŌĆØ he tells Clark in the book.

He knew that MikeyŌĆÖs parents had a drinking problem. That explained why in all the years they were best friends, Clark had never once stepped foot in MikeyŌĆÖs house.

Higgins filled in little bits and pieces that didnŌĆÖt quite complete the full picture but provided a kaleidoscope, which is how Clark describes ŌĆ£A Perfect Loss.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£A kaleidoscope with shards,ŌĆØ he said, referring to the colored angled mirrors that cast different lights and distortions to what you are seeing.

ThatŌĆÖs sort of how Clark saw life on B Street when he was growing up. One kidŌĆÖs triumph could be anotherŌĆÖs trauma.

ŌĆ£I wrote it like I lived it,ŌĆØ he said, and he hopes that if his B Street friends read it, they will see themselves.

ŌĆ£I would like to think if they were to read it they would say I captured what happened to them.ŌĆØ

About Harry Clark: Clark and Schuldmann retired their innovative classical music-meets-theater program Chamber Music Plus in 2011 after 40 years. They lived for a few years in Green Valley before moving to Shaker Heights, Ohio, in 2023. ŌĆ£We wanted one more adventure in our life,ŌĆØ said the 76-year-old Clark.