University of Arizona researcher Greg Leonard says now is the time for Tucsonans to see what could be the brightest comet of the year ŌĆö and he ought to know.

HeŌĆÖs the reason itŌĆÖs called Comet Leonard.

Leonard discovered the comet on Jan. 3, during his regular shift on Mount Lemmon with the Catalina Sky Survey, a NASA-funded, UA-run mission to find and track potentially hazardous near-Earth objects.

His was the first new comet discovered anywhere on Earth in 2021, and within a few days of spotting it, he learned that its orbit might bring it close enough to be ŌĆ£backyard visible.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs a rare thing,ŌĆØ Leonard said. ŌĆ£For me personally and professionally, itŌĆÖs like hitting the cosmic jackpot.ŌĆØ

Starting Thursday and lasting through the weekend, Comet Leonard should appear at dusk low in the west to southwestern sky between the horizon and an unmistakably bright planet Venus.

People are also reading…

ŌĆ£This will be the only week (when) weŌĆÖll have a chance for naked-eye viewing,ŌĆØ Leonard said.

Just donŌĆÖt expect too much from the researcherŌĆÖs namesake space snowball. It probably wonŌĆÖt look like much without the aid of a telescope or binoculars. If it is visible to the naked eye at all, it will likely show up as little more than a fuzzy star.

With some magnification, though, the cometŌĆÖs tail should be visible, he said.

The comet has already come as close to us as it ever will, streaking past our planet on Sunday at a speed of 44 miles per second and with a comfortable cushion of more than 21 million miles ŌĆö or roughly 88 times the distance between the Earth and moon.

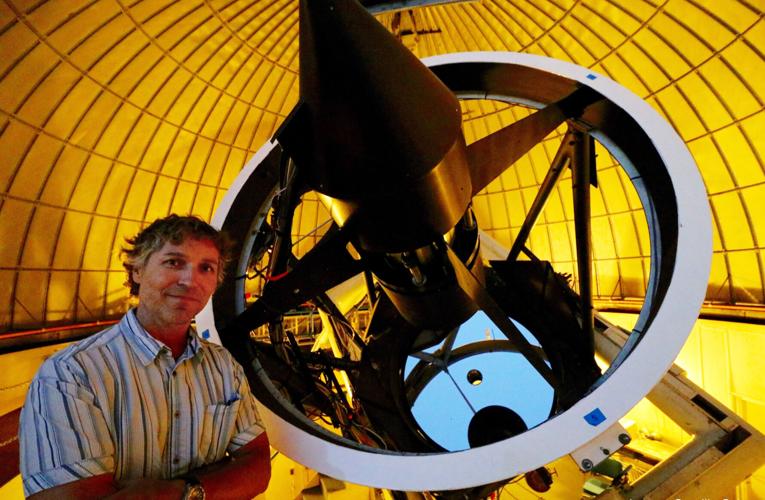

University of Arizona researcher Greg Leonard poses with the┬Ā1.5 meter Catalina Sky Survey┬Ātelescope on Mount Lemmon he used to discover a comet that just passed by the Earth.

Last weekend, when the comet still appeared in the morning sky, Leonard said he could just barely see it with his own eyes from the top of Mount Lemmon. ŌĆ£It was very, very incipient, but it was there,ŌĆØ he said.

ThereŌĆÖs a chance it could grow brighter in the coming days, as sunlight shines through the ice and dust of the cometŌĆÖs corona and tail in a process known as ŌĆ£forward scattering.ŌĆØ

Or it may continue to dim as it streaks away from us, Leonard said. ThatŌĆÖs the thing about comets: Their behavior can be unpredictable.

ŌĆ£As a wise astronomer once said, ŌĆśComets are like cats ŌĆö both have tails and both do precisely what they want,ŌĆÖŌĆØ he said.

Comet Leonard originated where most comets do: in the Oort Cloud of icy objects that marks the most distant edge of the solar system.

It has been ŌĆ£on approachŌĆØ to the sun for the past 40,000 years or so, with an orbit that suggests it circled past this way at least once before about 80,000 years ago.

It wonŌĆÖt be back this way again, Leonard said.

On Friday, it is expected to fly close enough to Venus to create possible meteor showers in the Venusian sky with dust from its tail. Then, early next year, it will slingshot around the sun and out of the solar system, never to return.

Comet Leonard and the M3┬Āglobular cluster photographed in the skies above Payson, Arizona.

This was the first of four comets Leonard has discovered this year alone, bringing his career total to 13 and counting after six years with the Catalina Sky Survey.

The survey leads the world when it comes to cataloging new comets and asteroids. Roughly half of all known near-Earth objects were discovered by survey staff members working in the mountains above Tucson over the past 23 years.

Because of the international scientific rules governing such things, all 13 of LeonardŌĆÖs comets automatically carry his name, followed by unique number sequences that spell out when they were first spotted.

Leonard said nearly every Comet Leonard he has found to date has been so obscure and so far away that it will never be widely seen from Earth or known to anyone outside of his narrow field of research.

These telescopes on Mount Lemmon have been used by the NASA-funded, University of Arizona-run Catalina Sky Survey to identify more new comets and near-Earth asteroids than any other site in the world.

Obviously, Leonard C/2021 A1 is the exception.

ThatŌĆÖs why the man who discovered it decided to spend a few days out at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument this week, camping with his wife, a telescope and a camera under some of the darkest skies they could find within a few hoursŌĆÖ drive of Tucson.

ŌĆ£We have to say hello and goodbye to Comet Leonard,ŌĆØ Leonard said.

Celestial alignments and shooting stars dominate this month of December! Mark these astronomy events down on your calendar and don't miss out.