For Tucson migrant advocate Dora Rodriguez, humanitarian work is the path to healing from tragedy, and a way to honor the friends who died beside her 45 years ago in the Southern Arizona desert, in a horrific border-crossing incident that galvanized TucsonŌĆÖs Sanctuary Movement in the 1980s.

ŌĆ£I heal in honor of my friends,ŌĆØ Rodriguez writes in her new memoir, ŌĆ£Dora: A Daughter of Unforgiving Terrain,ŌĆØ released Saturday. ŌĆ£I heal because, for some reason, I was chosen to live.ŌĆØ

Rodriguez recounts, in harrowing detail, the brutal days of walking unprepared through the Arizona desert, misled by smugglers about the length and difficulty of the journey. They carried just 18 jugs of water for the 26 Salvadoran asylum seekers and four smugglers, which quickly ran out. Rodriguez was one of the 13 asylum seekers who survived.

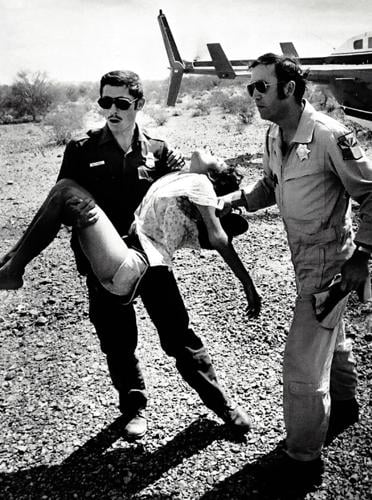

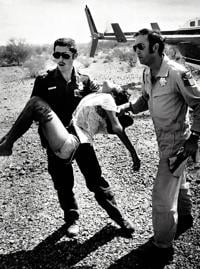

Rodriguez scheduled her book release for July 5, the 45-year anniversary of the day she was rescued by border agents and other law enforcement, likely minutes from death, nurses later told her.

People are also reading…

Much of RodriguezŌĆÖs memoir focuses on her childhood in El Salvador, and the escalating civil war that forced her, as a 19-year-old community organizer, to leave behind her tight-knit family in 1980 and flee to the U.S.

RodriguezŌĆÖs story culminates in her present-day devotion to humanitarian-aid work, including in immigration detention centers and the borderlands of Sonora and Arizona, where sheŌĆÖs become a beloved humanitarian leader.

ŌĆ£Dora is one example of how Central Americans have led some of the most important movements for social justice in the U.S. in recent years,ŌĆØ said Liz Oglesby, associate professor of Latin American Studies at the University of Arizona. She is ŌĆ£a beacon of compassion in southern Arizona.ŌĆØ

It wasnŌĆÖt until 2015, amid rampant dehumanizing rhetoric about immigrants from then-candidate Donald Trump and his supporters, that Rodriguez said she felt safe enough, and outraged enough, to speak publicly about her near-death experience and the terror that prompted her to flee her home, an account that sheŌĆÖd never even shared with her five children.

Four decades later, RodriguezŌĆÖs eyes still fill with tears when she describes leaving her mother and three younger siblings, after it became clear Rodriguez was in immediate danger and could bring risk to her family, too.

Tucson migrant advocate Dora Rodriguez at 19 years old on July 5, 1980, when she was one 13 people who survived a horrific border-crossing incident that galvanized TucsonŌĆÖs Sanctuary Movement. Her new book recounts her childhood in El Salvador, her decision to flee the right-wing governmentŌĆÖs violence and how sheŌĆÖs channeled the trauma of a life-changing tragedy into her devotion to humanitarian work.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs like leaving your soul behind,ŌĆØ Rodriguez said Wednesday, at Mercado San Agust├Łn on TucsonŌĆÖs west side.

In the late 1970s, El SalvadorŌĆÖs military was targeting anyone suspected of supporting the left-wing resistance, especially young people. Masked men with rifles marched through her neighborhood, part of a growing army of ŌĆ£death squadsŌĆØ who disappeared and killed suspected revolutionaries on behalf of the conservative government, which was backed by the United States, she said.

Suddenly, RodriguezŌĆÖs involvement in a social-justice youth group, and her high school sweetheartŌĆÖs membership in a teachersŌĆÖ union, were dangerous affiliations. Three of her friends were executed for their work as health educators.

In March 1980, Salvadoran Archbishop ├ōscar Romero was assassinated at the altar, one day after he gave a sermon imploring military members to stop killing civilians. Civilian deaths numbered 75,000 over the course of the 12-year civil war.

Rodriguez wants readers to understand the reality of forced migration, and the pain of leaving everything one has known.

ŌĆ£I didnŌĆÖt want to leave, but I also didnŌĆÖt want to die,ŌĆØ she writes in her memoir. ŌĆ£I didnŌĆÖt see any other path forward.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśDonŌĆÖt die on meŌĆÖ

RodriguezŌĆÖs memoir begins in 2024, with one of her annual visits to the site where her friends died, in a wash east of Arizona 85 in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The site is now marked by 13 crosses, crafted by Tucson artist Alvaro Enciso, in honor of those who didnŌĆÖt make it.

Dora RodriguezŌĆÖs son Trever designed the cover of her new memoir, ŌĆ£Dora: A Daughter of Unforgiving Terrain,ŌĆØ released July 5, 2025.

There, Dora spoke to visiting college students about three young sisters, at ages 12, 14 and 16, who died that day in 1980. The younger girls had become like little sisters to Rodriguez over the course of their journey from El Salvador. But she was powerless to save them at the end, she told the college students.

In her memoir, Rodriguez describes lying under the spindly branches of a palo verde tree before losing consciousness. She awoke to a uniformed man yelling in her face, ŌĆ£DonŌĆÖt die on me!ŌĆØ amid a flurry of rescue vehicles and law enforcement officers.

Rodriguez said the only reason she and her fellow survivors werenŌĆÖt deported back to El Salvador ŌĆö which almost certainly would have meant death for having fled the right-wing government ŌĆö was because they could testify against the surviving smugglers who had led the group to the desert, before abandoning them.

The survivors were seen as threats to the Salvadoran regime, because they spoke of the reality facing the Salvadoran people under the repressive government, which was supported by the U.S. in the name of fighting ŌĆ£communism,ŌĆØ Rodriguez said.

In reality, ŌĆ£that war was solely for poor people fighting for their rights and for their land,ŌĆØ she said.

The U.S. wouldnŌĆÖt offer asylum to refugees from Central America because it would have forced the U.S. to acknowledge its direct role in supporting the violent regimes from which people were fleeing, said Rodriguez, who eventually gained citizenship through marriage.

When she was still hospitalized after her rescue, ŌĆ£the Salvadoran Consul General came and treated me like I was an enemy of my country,ŌĆØ Rodriguez writes. ŌĆ£The publicity we were receiving for leaving the country and many of us dying was a national embarrassment to our government.ŌĆØ

Rodriguez hopes her memoir could become part of college curricula, helping educate and inspire a new generation of humanitarians.

The root causes of migration are too-often overlooked, as is the role of the U.S. policies in destabilizing migrantsŌĆÖ countries of origin, said Abbey Carpenter, a migrant advocate and former higher-education administrator, who co-wrote RodriguezŌĆÖs memoir.

ŌĆ£Ideally this book can be used by young people in educational setting to study whatŌĆÖs led people to have to make these choices, and what can we to do help in the future to help them not have to make that deadly choice,ŌĆØ she said.

Humanitarian work

Within moments of sitting down in Mercado San Agust├Łn on Wednesday, Rodriguez was approached by a smiling young man and the two joyfully embraced. Isac was an asylum seeker from Mexico and a former detainee at the La Palma detention facility in Eloy, when he was 19. HeŌĆÖs one of the many asylum seekers for whom Rodriguez has helped secure bond money, and she acted as his sponsor so he could be released in 2019.

The serendipitous reunion is nothing unusual for Rodriguez, who stays in touch with countless people whom sheŌĆÖs aided over the years. SheŌĆÖs especially proud of Isac, who is now bilingual and works in migrant aid, Rodriguez told the Star.

Dora Rodriguez is the founder of Tucson-based nonprofit Salvavision, which aids asylum seekers and deportees, and co-founder of Casa de la Esperanza, a resource center in the Mexican border town of S├Īsabe, Sonora.

ŌĆ£HeŌĆÖs an example of how, if you give someone a chance, you will see the beauty in this human being,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£Before we are migrants or asylum seekers or refugees, we are a person.ŌĆØ

Helping others became a way for Rodriguez to heal from the trauma she experienced herself, she said. After years of hosting asylum-seeking families in her home, Rodriguez threw herself into migrant-aid work. She helped raise bond money for detained asylum seekers and regularly visited detention centers to hear their stories, which she passed on to immigration lawyers.

Rodriguez eventually took over and expanded an existing program of the El Salvador consulate in Tucson, turning it into the nonprofit , which continues to aid asylum seekers and deportees today.

In 2021, in partnership with Tucson Samaritan Gail Kocourek, Rodriguez established the ŌĆ£Casa de la EsperanzaŌĆØ resource center in S├Īsabe, Sonora, a tiny town that was overwhelmed by migrants who were being immediately expelled from the U.S. under the Title 42 protocols, without an opportunity to request asylum.

Rev. John Fife, now pastor emeritus at Southside Presbyterian Church, told the Star that RodriguezŌĆÖs efforts in S├Īsabe, coordinating with local residents and officials, was ŌĆ£miraculous.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs the most amazing job of organizing IŌĆÖve seen on that border,ŌĆØ Fife said.

RodriguezŌĆÖs memoir highlights FifeŌĆÖs role as one of the leaders of the Sanctuary Movement in Tucson in the 1980s, in its early days at the time of the tragedy in Organ Pipe. Modeled after the Underground Railroad, the Sanctuary Movement helped shelter, and protect from deportation, thousands of Central Americans who were increasingly fleeing to the U.S., which refused to offer them asylum protection.

Fife recalled first meeting Rodriguez when she was freed from jail after her rescue. Fife had helped raise money for her bond and then reconnected with her decades later, as she started volunteering with the Tucson Samaritans, Humane Borders and No More Deaths.

He praised ŌĆ£her commitment to continue to help refugees and migrants in every way she can, and with a passion drawn out from her own experience in Organ Pipe Cactus Monument,ŌĆØ he said.

RodriguezŌĆÖs philosophy at the heart of her memoir encourages every-day people to take whatever small actions they can to help others, including those fleeing war and violence. That can mean volunteering, donating or something as simple as offering to pick up groceries for a family too scared to leave home, due to heightened immigration enforcement, she said.

In times of despair, ŌĆ£itŌĆÖs incredible how that can give you some peace,ŌĆØ Rodriguez said.

The message is a profound one for co-writer Carpenter, a volunteer with Battalion Search and Rescue, which searches for distressed migrants and human remains in the borderlands. Like many, Carpenter said she can struggle with hopelessness, especially in todayŌĆÖs overwhelming poltiical climate.

RodriguezŌĆÖs constant forward motion, and focus on solutions, is a guiding force, Carpenter said.

ŌĆ£She doesnŌĆÖt seem to give up hope,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£I get so frustrated when I look at the big picture of what has to be changed and I think, ŌĆśI canŌĆÖt.ŌĆÖ But I can do this: I can search in the desert. I can do humanitarian work. ... Find what you can do, and do it. Dora is a role model for that.ŌĆØ

Later in her memoir, Rodriguez returns to her 2024 visit to Organ Pipe, where she speaks to the college students, some of whom were by then in tears.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs hard to give back when you think you have nothing left,ŌĆØ she told them. ŌĆ£But youŌĆÖll be amazed by how much you can give once you realize that giving can heal you. ThatŌĆÖs been my salvation.ŌĆØ

Photos: The Sanctuary Movement in 1984

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana", Jim Corbett, "Jorge" and "Carlota" ,(l-r) travel in a car driven by Sanctuary volunteers from Hermosillo to Nogales, Sonora where they will saty in a safehouse and wait to cross the border into the U. S. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

During the hike following her border crossing "Juana" stops to empty rocks from her shoe during her hike across the thick vegetation and rough terrain near the Mexico/US border. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

During the hike following her border crossing "Juana" hustles through the thick vegetation and rough terrain near the Mexico/US border. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" climbs the desert border fence from Sonora, Mexico in to Arizona with the help of Jim Corbett, a member of the Sanctuary Movement during the summer of 1984. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Guatemalan refugee "Juana", trying to remain inconspicuous, reads a newspaper in the Mexico City Airport during her travel to America in the summer of 1984. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" catches a nap during the first airplane flight of her life from Mexico City to Hermosillo, Sonora in the summer of 1984. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Guatemalan refugee "Juana" follows Jim Corbett up the last leg of her journey through the desert towards her freedom. They would be met members of the Sanctuary movement and driven to Tucson. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Guatemalan refugee "Juana" lies low in the back of a camper, keeping out of sight oif passersby, outside Bisbee, Arizona. Juana had just crossed the border fence where she hiked through the desert and was picked up by members of the sanctuary movement and driven to Tucson. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Sanctuary founder and guide Jim Corbett, left, holds a midnight meeting with "Jorge" and "Carlota" in Mexico City to discuss travel plans for their journey to America. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" mops the floors at a Nogales, Mexico safehouse during an eight day wait to cross into America with the help of members of the Sanctuary Movement.. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" stops to rest during her hike across the thick vegetation and rough terrain near the Mexico/US border. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" sits in a safehouse in Nogales, Mexico waiting to cross the desert border fence into Arizona with the help of members of the Sanctuary Movement.. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" tries on a hat at a Nogales, Mexico safehouse during an eight day wait to cross into America with the help of members of the Sanctuary Movement.. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Sanctuary founder and guide Jim Corbett stops for a rest during his desert crossing hike. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Jorge" and "Carlota" wait in a Nogales, Arizona church to continue their journey to Tucson. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Sanctuary founder and guide Jim Corbett, right, meets Guatemalan refugee "Juana" in a Mexico City hotel room to discuss travel plans for their journey to the United States. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" stands in front of Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson where she was given safe haven by the Sanctuary Movement.

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" hurries along an Hermosillo street to meet a volunteer who will drive her north to a border safehouse. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Jorge" reads in his "room" at a Nogales, Mexico safehouse during an eight day wait to cross into America with the help of members of the Sanctuary Movement.. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Waiting at a safehouse to be taken to the U.S. "Juana" recounts her story of rape and torture at the hands of Mexican guards. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Jorge" watches television at a Nogales, Mexico safehouse during the wait to cross into America with the help of members of the Sanctuary Movement.. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Juana" is greeted by a volunteer at Southside Presbyterian Church following her crossing into America with the help of members of the Sanctuary Movement. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

"Carlota" holds an id card she used to cross the border in Nogales, Mexico. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Rev. John Fife of the Southside Presbyterian Church. He is one of the founders of the Sanctuary movement.

"Road to Refuge" special report in 1984

Jorge and Carlota, having crossed the border with fake identification cards are greeted by family members upon their safe arrival in Tucson. Photo from the 1984 series "Road to Refuge" documenting the travels of Guatemalan refugees from Mexico city to Tucson by means of an "underground railroad".